Sysunit

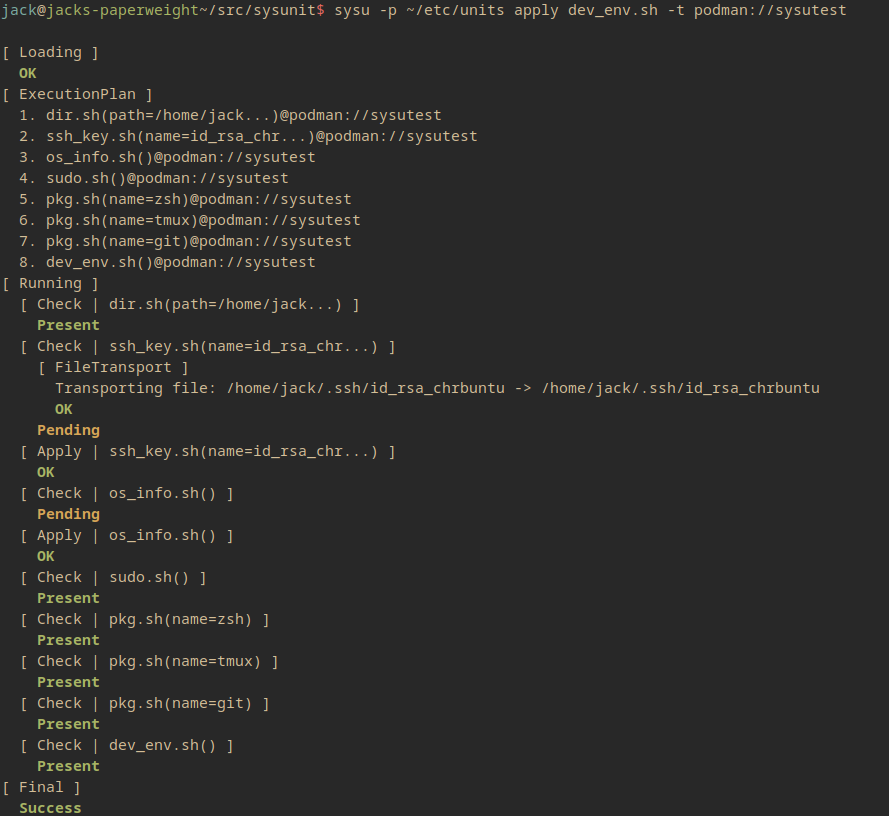

Sysunit is a minimal state management tool for POSIX systems. It's useful for things like wrangling your development environment, configuring servers, building code, provisioning containers and IoT devices, and automating deployments.

Instead of introducing a new language or requiring complex templating logic in configuration files to define desired state, Sysunit uses composable shell scripts to define units of change. This makes it easy for anyone familiar with basic shell programming to pick up (this includes LLMs!) and units can be run against spartan systems such as devices running busybox or alpine containers.

Qualities

- Minimal: Sysunit is a single binary with no dependencies.

- Agentless: Commands are streamed to target systems over anything that can intepret shell. This includes SSH, Docker, Podman, and even serial connections.

- Aproachable: There's only a couple concepts on top of basic shell scripting to learn here.

- Fast: Sysunit is written in Rust, and runs only one process per target system.

- Idempotent: Units are idempotent, so they can be run multiple times without changing the system state.

- Composable: Units can accept parameters, depend on other units, and emit values to their dependees, making this tool suitable for fairly complex workflows.

Limitations

- Sequential: Sysunit currently only runs one unit at a time. This is a only a limitation of the CLI, and the architecture will allow for parallelization with alternative interfaces.

- Stateful: This isn't Nix, and only provides idempotency checks as a way of avoiding the pitfalls of stateful configuration management.

- Small-scale: This tool is not intended for managing very large fleets of systems. The CLI will become hard to understand with more than a few dozen, and the process-per-target model will fall over at some point beyond that.

- Batteries Not Included: Sysunit is oriented at folks comfortable with POSIX systems currently, so it doesn't have any built-in units. A contrib repo of oft-repeated units is likely to emerge with traction.

Installation

Sysunit is oriented towards the Rust community until it reaches version 1.0, so it is only available via Cargo for now:

cargo install sysunit

Basic Operation

Given this basic unit:

# foo_file.sh

check() {

if [ -f /tmp/foo ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() touch /tmp/foo;

remove() rm /tmp/foo;

sysunit apply foo_file.sh will ensure that /tmp/foo exists on the local system,

and sysunit remove foo_file.sh will remove it.

Read the guide for approachable information on how to write and compose units, or the cookbook for a look at more sophisticated usage.

Guide

This is a slower introduction to Sysunit, and assumes only a basic understanding of shell scripting. Folks who like to puzzle things out for themselves might gain a more rapid familiarity from the cookbook.

The examples here are updated frequently with development of Sysunit and not always, thoroughly tested, so open a github issue if they give you trouble, or if you have a suggestion for other improvements.

Units

A Unit is a shell script which invokes various hooks that Sysunit will call throughout a run. These are, in order of their execution:

- meta: Provides metadata about the unit, such as its name, description, and parameters that it accepts.

- deps: Lists the units that this unit depends on.

- check: Determines if the unit needs to be applied or removed

- apply: Applies the unit to the system

- remove: Removes the unit from the system

Let's start with a basic example and go from there. Here's a simple unit that puts the current time into a file.

# foo_file.sh

apply() {

echo "Writing the current date to /tmp/foo"

date > /tmp/foo;

}

Running sysunit apply foo_file.sh will run the apply hook, which will write

the current date to /tmp/foo.

Note that the output from your unit is captured when doing this, and is only displayed if the unit fails to help you diagnose issues.

You can increase the verbosity of Sysunit with the --verbose flag to always

include this output, which can be helpful for monitoring the progress of

units that will take a long time to execute. Just like in a shell script,

output from commands executed in your unit will also be included, so if

you invoke a package manager for example, you can see what it's doing

while your unit executes with this method.

Note

Sysunit is only intended to handle printable characters! Outputting arbitrary binary can cause issues with its handling of output, and may cause your unit to fail.

See How It Works for more information on why this is the case.

Idempotency

The unit above is not idempotent, so Sysunit will run it every time you call

sysunit apply foo_file.sh. To make it idempotent, you can add a check hook.

Let's also provide a remove hook so sysunit can remove the file.

# foo_file.sh

check() {

if [ -f /tmp/foo ]; then

echo "Found /tmp/foo"

present

else

echo "Did not find /tmp/foo"

fi

}

apply() {

echo "Writing the current date to /tmp/foo"

date > /tmp/foo;

}

remove() {

echo "Removing /tmp/foo"

rm /tmp/foo;

}

Now when you run sysunit apply foo_file.sh, Sysunit will check if /tmp/foo

exists, and if it does, it will not run the apply hook. If you run sysunit remove foo_file.sh, it will remove /tmp/foo, only if it already exists.

Handling Errors

Sysunit runs unit hooks in a shell with set -e -u, meaning that any non-zero

exit status from your commands will cause the unit to fail, and any output to

be printed to aid with diagnosis of the issue. Let's look at a unit that will

fail:

# fail.sh

apply() {

echo "I have chosen not to comply"

false

}

On running this, you should see output to the terminal telling you which unit failed, and include its output.

If the output is not enough to go off of, you can invoke sysunit with

--debug which will include trace output from your script (this is just set -x in the subshell that your unit runs in.)

Parameters

Units are more useful if when they can be re-used. For example, you might have a unit that installs some package on the target system:

# pkg.sh

check() {

if dpkg -l | grep -q vim-nox; then

present

fi

}

apply() {

apt-get install -y vim-nox

}

It would be really troublesome to have to copy this unit for each package we want. Let's parameterize it so it can install any package we want:

# pkg.sh

meta() {

params !name:string

}

check() {

if dpkg -l | grep -q $name; then

present

fi

}

apply() {

apt-get install -y $name

}

Here we've introduced a new hook, meta, which is used to tell sysunit about your

unit. The meta hook supports the params function, which takes a list of

parameter definitions. In this case, we've defined a single parameter, name,

which is a string, and is required as denoted by the ! prefix.

When you run this unit, you'll need to provide a value for name, which can be done

via the sysunit CLI since this is the only unit we are invoking for now:

sysunit apply pkg.sh --arg name=tmux.

If it is invoked with in invalid type, sysunit will exit with an error message.

The types of parameter currently allowed are:

- string: Any string value

- int: A numerical value in base 10 format with no decimal

- float: Any numerical value in base 10 format, must include a decimal

- bool: Either

trueorfalse

More complex types such as arrays are not currently supported, but a JSON type to allow structured data to validated by sysunit and handled in scripts that can make use of them through jq or similar. For the time being, using strings is recommended.

Optional Parameters

In the example above, the $name parameter is required, so Sysunit guarantees that

the shell parameter will be set when our hooks are run. If we make the parameter

optional, we need to take care in our shell script to handle the case where it

is empty, or it will fail due to the set -u environment it runs in.

# name_file.sh

meta() {

params name:string

}

apply() {

# Default to Jack if no other name is provided

echo ${name:-Jack} > /tmp/my_name

}

Other Metadata

The meta hook also allows specifying some additional Metadata which will help

document your units.

# foo_file.sh

meta() {

author "Jack Forrest"

desc "Writes some stuff to /tmp/foo"

version "0.5.0"

}

None of this is required, or used much within sysunit currently, but it's readily legible and will likely be presented in a more useful form by the Sysunit CLI soon.

Dynamic Metadata

It is possible to script the meta hook, so you could dynamically define parameters based on the environment. All hooks for a unit are executed on the target system, so facts are available here.

However, this is heavily discouraged. It will be confusing to yourself and other users of your units if these things change between invocations.

Dependencies

Single units can be useful, but the goal of Sysunit is to allow them to be easily composed to express complex desired system states. This is mostly accomplished by defining dependencies that your unit requires.

Let's use our package installation unit from the previous section, and invoke it with various arguments to set up a development environment for writing Python:

# dev_env.sh

deps() {

dep pkg.sh name=git

dep pkg.sh name=python3

dep pkg.sh name=tmux

}

When we run this with sysunit apply dev_env.sh, sysunit will use the deps

hook to determine that before dev_env.sh can be considered applied, three

instances of the pkg.sh unit must be applied first, each with the provided

name argument. Each of these dependencies will have their check hook run

before applying, and apply will only be run if it does not indicate that the

unit is already applied.

Note that this unit does not provide an apply hook, so Sysunit will do

nothing by default after the dependencies are satisfied, units like this

are only used as a sort of manifest to define a set of units that should be

applied together.

Unit Path

By default, Sysunit will look for units in the current working directory, but

you can specify colon-separated paths in which units can be found either with

the --path or p flag, or by setting SYSUNIT_PATH in your environment.

Dependency Resolution

Unit instances are resolved into a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) before execution. A unit instance is differentiated by a combination of its target (explained in another section) and its arguments, and an instance is executed only once per sysunit invocation. Let's see how this works in practice:

#foo_file.sh

deps() { dep scratch_dir.sh };

check() {

if [ -f /tmp/scratch/foo ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() echo "helloooo" > /tmp/scratch/foo;

#cat_pic.sh

check() {

if [ -f /tmp/scratch/cat.jpg ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() curl -o /tmp/scratch/cat.jpg https://placekitten.com/200/300

#scratch_dir.sh

check() {

if [ -d /tmp/scratch ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() mkdir -p /tmp/scratch

#project_files.sh

deps() {

dep foo_file.sh

dep cat_pic.sh

}

When we run sysunit apply project_files.sh, Sysunit will run the units in this order:

scratch_dir.shfoo_file.shcat_pic.shproject_files.sh

Note that scratch_dir is only run once, even though two units include it in their deps.

Dynamic Dependencies

When we define parameters that our unit can accept, they are injected prior to running the

deps hook. This allows us to define dependencies that are based on parameters of our unit:

#cat_pic.sh

meta() {

params !url:string

}

deps() {

if $url | grep -q '^ssh'; then

dep pkg.sh name=scp

else

dep pkg.sh name=curl

fi

}

apply() {

if $url | grep -q '^ssh'; then

scp $url /tmp/scratch/cat.jpg

else

curl -o /tmp/scratch/cat.jpg $url

fi

}

As with all other hooks, the deps hook can run any arbitrary shell code, and is executed

on the target system

Unlike Metadata, deps are intended to be dynamic, and that capability is very powerful. However, some users may not desire the lack of determinism in knowing which dependencies will be run when they invoke a unit. The Execution Plan output intends to provide clarity on what dynamic units have been selected, but use of this feature can be avoided for those who don't desire it.

Dynamic Parameters

We can also pass our dynamic parameters directly down to our dependencies:

#foo_file.sh

meta() {

params !directory:string

}

deps() {

dep dir.sh directory="$directory"

}

apply() {

touch $directory/foo

}

#directory.sh

meta() {

params !directory:string

}

apply() mkdir -p $directory;

Running this unit with sysunit apply foo_file.sh --arg directory=/tmp/ will first

create the /tmp/ directory, and then create the foo file in it.

File Dependencies

A unit may also depend on files. This is useful when you need to ensure that a file exists on the system the unit is to be run on. Files are transported from the local system to the target system via an appropriate subcommand.

#ssh_key.sh

meta() {

desc "Sets an ssh key retrieved from the local system up on the remote system"

params !name:string

}

deps() {

dep dir.sh path=/home/jack/.ssh

file src=/home/jack/.ssh/$name, dest=/home/jack/.ssh/$name

}

apply() {

chmod 600 ~/.ssh/$name

}

Under the hood, commands like podman cp or scp are used to transport the file, so

entire directories can be given.

If a relative path is given for the source, the directory of the unit is used as the base path.

If a relative path is given for the destination, the home directory of the user the unit is run as is used as the base path.

Limitations

- Files can only be transported from the local system to the target, not from other systems.

- Tilde expansion is not supported.

Captures

While parameters are sufficient for cascading data down from parent units, sometimes parent units need to get data back from their children. Captures accomplish this by allowing a unit to emit values, which can be captured by their parents when desired. This allows us to do things like get 'facts' about the system from shared units, or to respond to recoverable error conditions.

#pkg.sh

meta() {

desc "installs a package, will use sudo to escalate priveleges"

params !name:string

}

deps() {

dep sudo.sh

dep os_info.sh -> !id:os_id:string

}

check() {

case $os_id in

debian)

if dpkg -l | grep -q "^ii $name"; then

present

fi

;;

alpine)

if apk info | grep -q "^$name"; then

present

fi

;;

*)

echo "This unit only works on debian and alpine"

exit 1

;;

esac

}

# Other operations skipped here, see cookbook for a more complete example of

# package handling.

Here, the line dep "os_info.sh -> id:os_id:string" tells sysunit that the

os_info.sh unit should be run, and that it is expected to emit a value named

id as a string which will then be aliased to the os_info parameter (the

alias is optional, we could have also specified -> id:string, but being able

to add context and avoid name collisions is nice.) This value is then available

in the pkg.sh unit via the $os_id variable.

Emitting Values

Now let's look at the os_info.sh unit pkg.sh depends on:

#os_info.sh

check() {

. /etc/os-release

emit_value id "$ID"

emit_value name "$NAME"

emit_value version_id "$VERSION_ID"

emit_value pretty_name "$PRETTY_NAME"

}

Here, the emit_value function is used to send key-value pairs to Sysunit, so

they can be provided to dependees. This can be called from check, apply or

remove hooks. We must ensure that all required values get emitted, but

optional values can be skipped. (For example, we may have values which are only

emitted if the unit is removed.)

Parameter Availability

Capture params are available in the check, apply, and remove hooks, but

not in deps or meta, since dependencies will not have run until after the

deps hook has completed.

Targets

So far, we've been running units against our local system, which is great for building projects or setting up development environments. However, Sysunit is also capable of targeting other systems via adapters. This capability can be used to do things like:

- Set up remote servers

- Configure and provision SoC devices

- Build Docker or Podman containers

- Automate deployments

Setting target via the CLI

When invoking a unit via the CLI, we can set the target explicitly with the --target flag.

sysunit apply foo_file.sh --target ssh://admin@my_server.net

The target is given as a URI, and the protocol portion is used to determine which adapter to use. Out of the box, Sysunit provides the following adapters:

ssh: Connects to a remote system via SSHdocker: Runs the unit in a Docker containerpodman: Runs the unit in a Podman container

Setting targets for dependencies

For more sophisticated workflows, it's desirable to have various units target different systems. This can be accomplished by setting the target for dependencies.

# dev_env.sh

deps() {

dep local://localhost:pkg.sh name=ssh

dep ssh://admin@my_server.net:pkg.sh name=python3

dep ssh://admin@my_server.net:pkg.sh name=tmux

}

When we run this with sysunit apply dev_env.sh, Sysunit will use the deps

hook to determine that we first need to install the SSH package on the local

system, and then install Python3 and tmux on our remote server.

Note that for adapters other than local, external binaries are invoked, so

ssh, Docker, or Podman may need to be installed on the host machine.

As with the local adapter, only one instance of an adapter per target is initialized per Sysunit invocation. This means that if you have multiple units targeting the same system, they will be run in the same session.

Target Inheritance

When a unit is run with a target, that target is inherited by its dependencies, so units don't need to explicitly set targets for their dependencies unless they need to target another system.

Dynamic Targets

As with everything else in dependencies, target strings are scriptable, so you can do things like dynamic inventory using parameters.

install_nethack.sh

meta() {

params !user:string, !host:string

}

deps() {

dep ssh://$user@$host:pkg.sh name=nethack

}

Path and Unitfiles

Sysunit will look for units in the current working directory by default, but provides more sophisticated lookup options enabling a great deal of flexibility in how you lay out your configuration.

Note

Units are always loaded from the host system, even when using adapters. They are streamed to target systems, but never copied.

Search Paths

Directories of units can be added to the search path with the --path or -p flags,

or via the SYSUNIT_PATH environment variable. These units can then be referenced

from other units with no path prefix.

For example, if you have /etc/units/foo.sh and /etc/units/bar.sh, foo may

reference bar with dep bar.sh

Unit Files

Individual files can be a pain when you have many small units, so Sysunit has the capability of parsing multiple units from a single file using a simple comment header format to delimit them.

# The header below indicates to sysunit that we're starting a new unit

# [ foo_file.sh ]

deps() {

dep ./dir.sh path=/tmp

}

apply() touch /tmp/foo;

# [ dir.sh ]

# We are now inside of the dir.sh unit

check() {

if [ -d $path ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() mkdir -p $path;

Relative Paths

Relative paths in units are resovled relative to the directory the unit resides in. It's probably best-practice to mostly use relative paths, so you can move your units around and disambiguate if you directories containing unrelated units to your search path.

When using relative paths, Unitfiles act just like a directory. If build_units.sysu is in

your search path and contains a unit named foo.sh, youc an reference it from another unit

with build_units.sysu/foo.sh. The .sh extension is optional, but recommended for the sake

of clarity.

Layout Recommendations

I personally maintain common units in a mixture of /etc/units for system-wide

config, ~/.local/etc/units for my user-specific stuff, ~/src/build for

units I use for a mixture of projects, and then ./units or ./Unitfile.sysu

for those specific to a certain project.

I have export SYSUNIT_PATH="/etc/units:~/.local/etc/units:~/src/build" in my

.bashrc to it easy to invoke any of the common ones from anywhere.

When I'm working in a project, I often invoke sysunit with -p ./units to include

those specific to my project.

Cookbook

Installing From Tarballs

Node.js is a dependency that I usually need to install from tarballs due to it being out of date in most package managers. Here's the unit I use to do that:

#node_install.sysu

# [ install.sh ]

meta() params !version:string;

deps() {

dep ./download_source.sh version=$version -> !dir:node_dir:string;

dep pkg.sh name=make

dep pkg.sh name=build-essential

}

check() {

if which node >/dev/null; then

present

fi

}

apply {

cd $node_dir

./configure

make

sudo make install

}

remove {

cd $node_dir

sudo make uninstall

}

# [ download_source.sh ]

meta() params !verson:string;

deps() {

dep pkg.sh name=curl

}

check() {

if [ -d /tmp/node_build/node-$version ]; then

present

fi

}

apply() {

mkdir -p /tmp/node_build

cd /tmp/node_build

url="https://github.com/nodejs/node/archive/refs/tags/${version}.tar.gz"

curl -L $url | tar -xz

cd node-$version

emit_value dir `pwd`

}

remove() {

rm -rf /tmp/node_build

}

This unitfile splits the job into two units so the node source isn't unnecessarily downloaded if there are errors.

It can be run with sysunit apply ./node_install.sysu/install.sh version=14.17.0

How Sysunit Works

Some of the things Sysunit does will the shell units can seem a bit magical, but there's only a couple of tricks going on here to get them to work.

Shell Execution

Sysunit simply pipes your scripts into a shell interpreter, potentially over some intermediary like SSH or Docker, runs its hooks, and parses its output to separate emitted values from regular output.

Execution of hooks from units is interleaved, since, for example, dependencies

need to be retrieved from a unit (which requires executing its deps hook)

before its check and apply or remove hooks are run. These hooks are all

run in subshells, so they don't affect the environment of other units.

Hooks

The shell environment hooks run in is set up with someting like this:

exec 2>&1

meta() : ;

deps() : ;

check() : ;

apply() : ;

rollback() : ;

dep() _emit dep $@;

author() _emit meta.author $@;

desc() _emit meta.desc $@;

params() _emit meta.params $@;

emits() _ emit meta.emits $@;

present() _emit present true;

emit_value() {

local key="${1:?key must be provided to emit_value}"

shift

_emit "value.${key}" "$@"

}

_emit() {

local key=${1:?key must be provided to _emit}

shift

local val="$@";

printf "\n\001${key}\002${val}\003"

}

Beyond this, the subshells have set -e -u (and maybe -x if you specify --debug) to

help catch errors, but there's really not much else going on for the execution of a single

hook.

Emits

Sysunit extracts various values from your units with emit messages, which are just bits of stdout output delimited with some non-printable characters so sysunit can differentiate it from diagnostic output that should be shown to the user.

These emit messages follow a format like this:

\001

<key>.<field>

\002

<message content>

\003

The whitespace is insignificant here. The key and field are used to indicate to Sysunit what kind of message is being emitted, and then the message content is handled appropriately to do things like set up dependencies or emit values to dependees.

About Sysunit

Sysunit is currently a solo side project by Jack Forrest.

It was born out of frustration with the unsuitability of more complex tools for simpler configuration tasks like setting up a new server or configuring environments more minimal than Ansible can target, and a desire for something more robust than the ad-hoc shell scripts I kept writing to do these jobs.

It started out as a shell script that just provided params to and parsed output from my other scripts. It was re-written in Python in 2020, and then again in Rust in 2022. In late 2024 some friends started using it, but I was pretty embarrassed by the throwaway code and some architectural flaws, so I re-wrote it again in async Rust and wrote some actual docs.

Now, in 2025, I think the shell-based paradigm has proven itself to myself and a few others, and the code-base has reached enough architectural stability that I figure it's ready for a wider audience.

This tool is shared in the hacker spirit, and does not aim to deliver a regimented approach to configuration management. It affords a lot of flexibility and direct control without faffing about with many abstractions, and its accepted that can mean footguns for some potential users. However, I'm always looking for better ways to do things if it doesn't mean trading too much power! Open a GitHub Issue with any feedback or recommendations.